Why do we need a gender lens to deal with COVID-19 risks and impacts on fisheries and aquaculture?

Because at this point of the pandemic, though we can’t fully depict what the consequences will be on both genders, we can ascertain that the coronavirus outbreak will hit women harder than men, threaten progress made in empowering women and deepen gender inequities already pervasive in the fisheries sector, write Natalia Briceño-Lagos & Marie Christine Monfort from The International Association for Women in the Seafood Industry (WSI)

On account of this, WSI will watch how the contagion and related economic downturn hits both genders in fisheries, aquaculture and the entire seafood value chain, and will examine more closely the situation that women encounter.

Global crisis

The pandemic is spreading all over the world and national responses vary greatly according to the different countries’ healthcare systems, capacities, quality of care and conditions of access.

One universal feature is that women are on the frontline of the battle against the virus in every country. With very few exceptions women represent a vast majority (70%) of the healthcare workforce, bear a large part of the responsibility for the care and education continuity of children when schools have closed and keep the family safe during this very uncertain time.

However, we must not forget that women in the food industry, particularly in seafood, are also part of this front line. They have a key role in ensuring food security for all.

The seafood industry’s gender division of labour: women more exposed to virus

Let us recall that women occupy a significant part of the fisheries workforce, representing half of the entire world labour force in this sector.

The FAO estimates that women comprise 15% of the harvesting workforce, 70% of the aquaculture workforce, and somewhere between 80 and 90% of the seafood processing workforce. In Africa and Asia, women also represent 60% of seafood traders and retailers.

Clearly women are fundamental agents in the organisation and functioning of the local, regional and global flows of seafood.

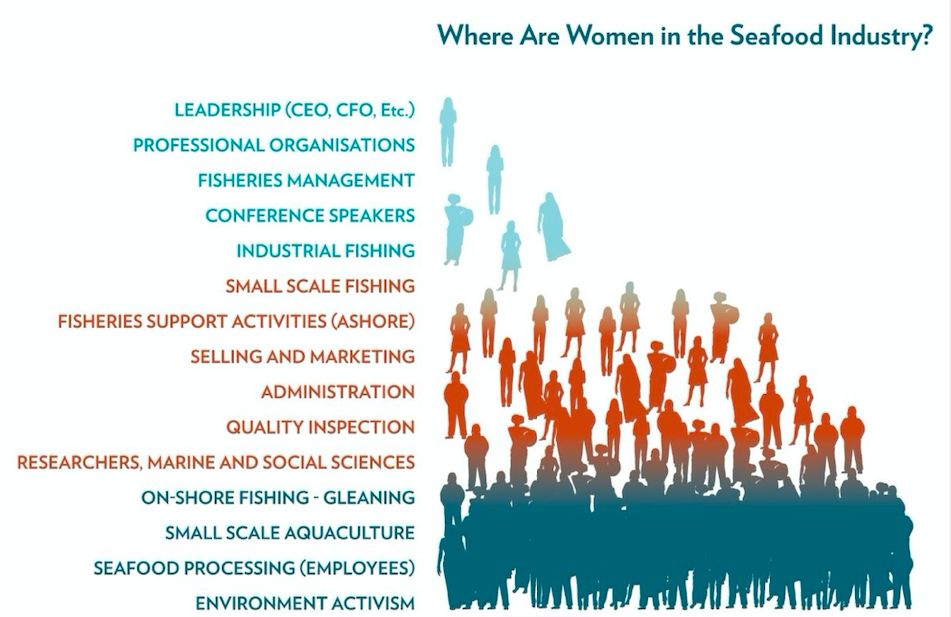

Furthermore, men and women occupy distinct roles along the seafood value chain. CEO, board members and fishermen are nearly all males. Whereas employees in processing plants, for example, shrimp peelers, are nearly all female.

The seafood industry shows a strong gendered vertical division of labour whereby a majority of ignored, invisible, unrecognized (IIU) women occupy low-revenue jobs and where top jobs are occupied mostly by men.

In that regard, the coronavirus will strike genders differently – these gender imbalances will shape the experiences of women and men affected by the pandemic, unequally.

Identifying the positions that most women occupy can already shed light on the impacts that this crisis will be having on them.

Women mostly present at the bottom may have to continue their working activities to get an income, the opportunity to stay at home like those at the top not being offered to them. Adding to this, occupations where women are located, in processing plants and retail markets, bring with them higher exposure to the virus.

One emergency response given by some companies is to protect their frontline employees processing seafood by ensuring decent and safe working environments with proper protective equipment. This requires changes in work routines, purchase in protective equipment and clothing. Not all companies will have complied with these strict recommendations.

Coronavirus and economic crash

In this world-wide pandemic, labour markets, seafood markets and other inputs (such as finances) will be deeply affected. Job losses, estimated at 25 million, says the ILO, will be inevitable.

The fall in business revenues will inexorably result in the reduction of costs by laying off workers, starting with temporary and casual ones disproportionally occupied by women. This is already happening in the Chilean salmon industry, for instance, which is reducing the production capacity of its plants by almost half, with layoffs already happening among precarious workers.

We have already seen the early effects on the seafood business and fishing communities relying on imports from China. The consequent rise in prices induces a severe disruption of local markets as seen in Cameroon or South Africa.

The widespread work-from-home movement will enable millions of workers to keep their jobs and their salary partly or fully. But this arrangement is largely available to white-collar workers.

In the seafood industry, those office workers protected by full-time work contracts are mainly men.

Women in low-paid jobs with insecure employment conditions are at greater risk of losing their income. When women lose their income, they severely cut budgets supporting the well-being of their children, households and communities (e.g. housing, food, healthcare or childcare).

Disruption along the seafood value chain

Who will be the most affected link in the chain when the seafood value chain will be disrupted?

How will the drop in landings and consequent fast-rising prices such as already observed in West Africa affect male fishermen, female processors, female retailers and the entire community?

How will the stop of movements of seafood impact the different categories of players?

We have already witnessed that exhaustion of marine resources has had a dramatic impact on women (in charge of processing, trading) and we fear similar disproportionate and discriminatory effects of COVID-19.

In order to answer these question and to put forward smart and resilient responses, we need gender-disaggregated data in the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. Efforts in this direction must also be made in the surveillance and monitoring stages of the pandemic. Effective responses need to be backed by quality data and evidence-based solutions.

Alongside this, women must be a part of the decision-making processes that public authorities will engage. As far as WSI is concerned we will set up a data collection program and organize a watch on the local and regional impact of the pandemic.

Very probable prospects in a highly uncertain future

The achievement of the 2030 SDGs will be critically hampered by the economic impacts of the coronavirus crisis.

We face the possibility that when resources are needed to combat the pandemic, the ability of countries to spend on other development priorities, such as combating climate crisis or gender inequality, will be severely constrained.

We run the risk that in this period of high economic turbulence leaders will think that gender equality (SGD 5) is not a priority, and that it can wait until the economy is looking up. This would amount to repeating past mistakes.

In overlooking the gender dimension of gender in the seafood industry, policymakers have in the past drawn wrong diagnoses on marine resources and economic management. Consequently, efforts to meet SDG14—Life below water—may well miss their target.

What is needed first and foremost is awareness on the fact that SDG 14 will not be attained if 50% of the population it affects is not taken into consideration. Gender must be embedded in all elements and targets of SDG 14 policy.

When we are ready to get back on our feet and get the blue economy going again—hopefully, a truly sustainable version of the blue economy—decision-makers must consider the gender organization of the industry.

We otherwise predict that responses will fail and increase inequalities between women and men. Research from other types of health crises has shown that leaving gender inequalities out of the crisis response has further compounded those inequalities.

WSI considers that if we want to find the most effective ways to deal with COVID-19, all workers, especially women need to be listened to and involved in building future responses.

Recent Comments