By: Chloe Irvine

Retired skippers John Arthur Irvine and Willie Williamson have more than 100 years of fishing between them. Both played a key role in progressing Whalsay’s pelagic fishing industry to what it is today. Here they share some of their stories with Chloe Irvine.

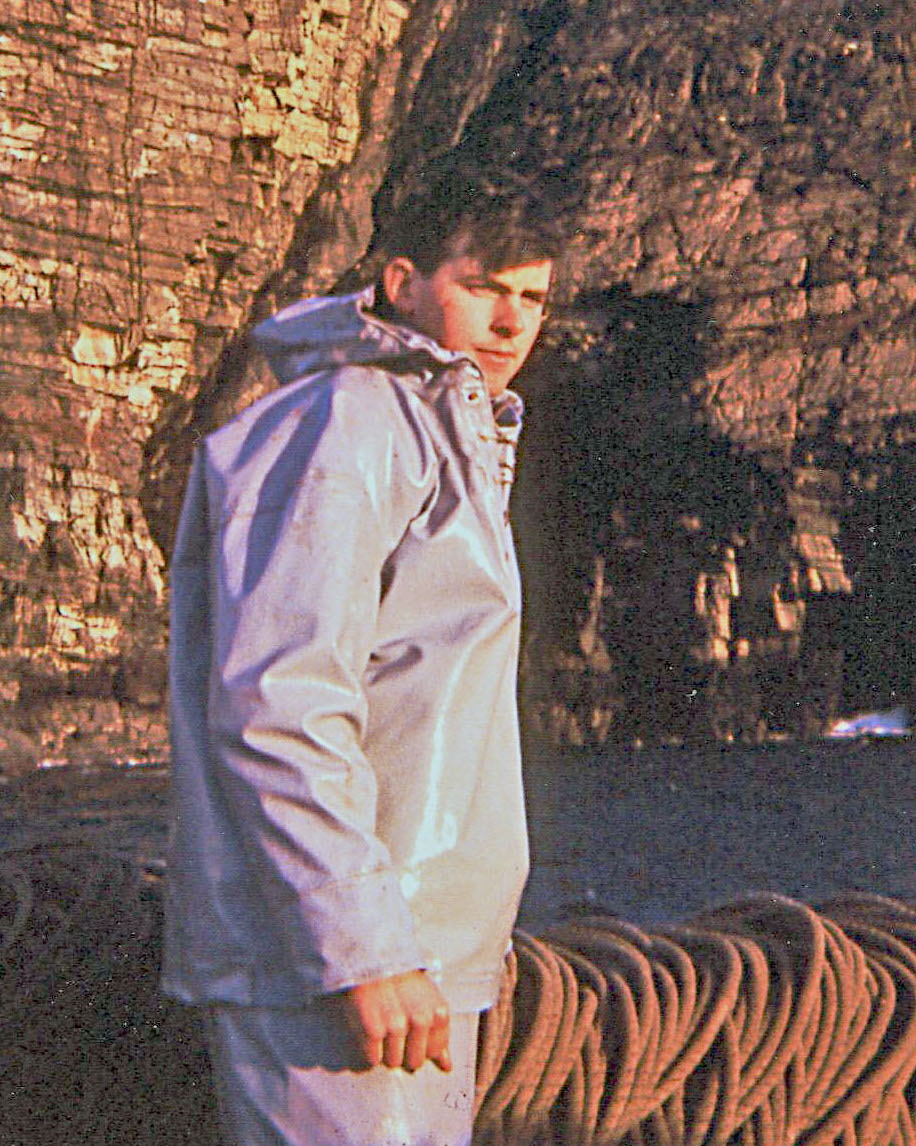

When John Arthur Irvine started his fishing career in 1959 at the tender age 15 as a cook on board the Fortuna there was little technology which could help the men finding the fish and also finding their way around the vast ocean.

They worked close to shore and learning from the older hands of how to navigate using fishing ‘meids’ was essential. When the first Decca navigators came in they helped a bit but they were a far cry from the satellite navigation that is the standard today.

Recalling those early fishing trips to John Arthur, now 77 years old, said it had been vital to take on board the lessons that the older generation had passed on.

“We didn’t even have a radar when we first went to Aberdeen, with stacked mist half of the time. The foghorn was at the end of the pier and somebody would go out and listen for it and we’d steer for that,” he remembers.

Seventy-four year old former skipper of the Research, Willie Williamson, nods in agreement at remembering those days when you had to listen your way through the fog.

“The likes of the old Research didn’t have a radar, I remember coming from the west of the Flugga with herring going to Lerwick. It was thick mist and I think we were ashore nearly three times!”

Throughout the next 50 years, both skippers became instrumental in introducing transformational changes to the Whalsay fishing industry, investing in new and larger vessels at critical times, enduring sleepless nights on the bridge and worrying about those loan payback terms.

For John Arthur there was never a question that the continual need to modernise was the only way to survive in the ever-changing industry.

“After spending a few months in the Fortuna, I went into the first Zephyr, which was sold in 1976. That boat was just 64 feet long, a little seine net boat, there was no shelters on the deck,” he says as he describes the early years.

“My father retired two years before we sold the first Zephyr. I was skippering for a few years, and then we got the first new boat for new owners, which was an 87-foot whitefish trawler.

“We had that boat for four years, then we sold her and got a steel boat made in Norway, a purse-netter catching mackerel and herring as opposed to whitefish, a big change.

“We struggled for a few years to meet the payments. That boat had a capacity of 500 tonnes. Then we got another boat, a bigger one still, it could hold about 16-17 hundred tonne of blue whiting.

“You just had to keep adapting the whole time. We had four Zephyrs before I retired and now we’ve got another one.”

Going from whitefish to pelagic wasn’t something they had “ever done before”, he continues his story, describing the financial implications of the move as “significant”.

“Getting a boat as expensive as that, you have to meet payments and the loan was from Norway. It was supposed to be a ‘low interest loan’ but it was 7.5 per cent. Interests here at that time were twice as much as that. We never got any financial help,” he recalls.

“When we went to get the first boat we owned ourselves, we had to find £12,500 each. You could have built a big house with that.

“It was a big gamble, and an even bigger gamble when we got the steel boat. £1.6 million was a huge quantity of money at that time.

“It was stressful, and then we couldn’t get our old boat sold for a while, so we had to get a loan from Clydesdale Bank which was twice as much.

“There were a lot of folk that thought we’d lost our wits. If we’d gone bankrupt, they would’ve taken everything we had. Our house would have gone, everything would have gone, we’d be left with the clothes we were standing up in.

“Even my father took half a share with us just to help out, they could have wiped him out too if it hadn’t gone the right way. The only help we got was from the boys in the LHD like Ritchie Simpson, he was a huge help to us.

“Most of my time at the fishing has been spent paying back loans.”

Willie, meanwhile, concedes that the strain of meeting the payments got to him on occasion. The period that stood out for him most was getting their second-hand boat for £11,000 to five years later buying the Venturous for £180,000.

At times there “wasn’t always a lot of fish around” which led to many sleepless nights, while 36 hours in the wheelhouse had been a “common” occurrence for him.

Like John Arthur, people had questioned his intentions “they couldn’t see that you could ever pay for it”.

“People would ask if I’d ‘really thought this through’. I said ‘Well we just have to get the boats and if we don’t get it paid for, then that’s just too bad. We have to do our best’,” he says.

Today’s generation have their own set of challenges getting into the fishing industry. John Arthur explains: “The disadvantage right now for the young ones, they have to buy licenses and buy quotas.

“When I first went into the fishing (…) all you needed to get a down payment on the boat itself and then get the fishing gear and away you went.

“Now, they have to buy a license and buy quota and it’s dearer than the boat. It makes it far more difficult.

“I think fishermen are at the very lower end of the scale for getting help, but they’re a good hand at helping themselves if they get any chance.”

Willie says he believes that it is now “almost impossible” for the young ones to get into the industry.

He goes on to criticise the Tory government and their long drawn approach to Brexit: “It’s really unfair the way these pelagic boats are being treated in comparison with the Icelandic, Faroese, Dutch.

“They’re fishing around here all of the time, yet our boats are tied up for 10 months of the year, the Faroese are fishing like 10 months of the year, it doesn’t seem right.

“They [the government] have it down for 2026 to try and get it worked out, I think they could’ve done it sooner than this.

“There’s far more cod around here than there ever used to be, you can’t get clear of it, yet they are having to import cod from Norway and Iceland. It really doesn’t make sense.”

Recent Comments